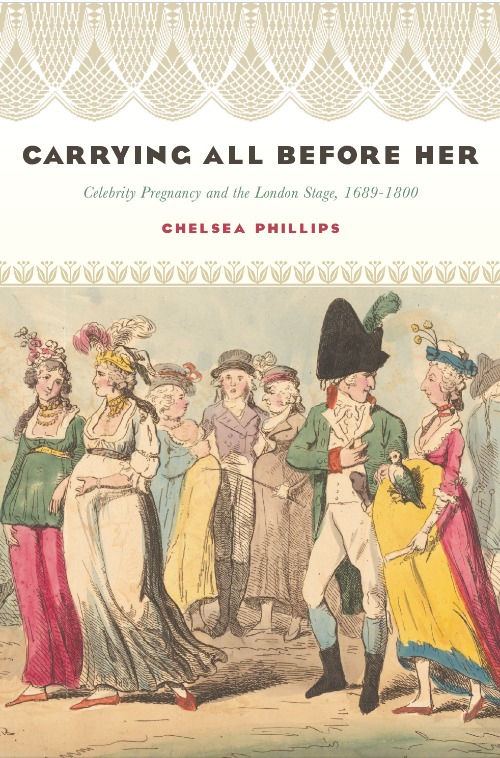

"Frailties of Fashion" (1793)

- Chelsea Phillips

- Jul 22, 2021

- 6 min read

Updated: Aug 30, 2021

This is part of a series of postings in the run-up to my book release on January 14, 2022. More information on Carrying All Before Her: Celebrity Pregnancy and the London Stage, 1689-1800 and pre-order available here. **discount code: RFLR19**

--

Being the first of my posts in the run-up to my book release, I thought we'd start with the cover image.

"Frailties of Fashion" is a British satirical print by Isaac Cruikshank published May 1, 1793. It shows a scene in a public park: a crowd of people, mostly women, stroll through the image dressed in a variety of fashions. To a person and regardless of age, they all appear to be visibly pregnant, from the girl and her doll positioned on the left of the drawing to the veiled older woman in purple near the center.

The women vary in their size and in the signs used to indicate their condition. The woman in yellow on the left is represented as pregnant through gesture and context more than size. The central figures swell delicately. Others, including (left to right) the little girl, the woman in white and pink, the older woman in purple, both background women on the right AND the woman who sports a bird on her belly all demonstrate a stage of pregnancy known as "the rising of the apron," when the belly was large enough to raise the front hem of one's garments.

Even the woman to the extreme right, visible only from the back as she exits the frame, is identified as pregnant through her posture, seeming to lean back and rest her right arm upon her belly.

There are evocative details throughout. The aforementioned bird (identified by M. Dorothy George as a variety of paroquet); the woman in brown whipping her rival's belly with a riding crop; the older man with the older woman kissing his cane/phallus, perhaps celebrating the fertility his companion's condition suggests. The virility of the other men is also emphasized: the man in green grips a substantial club rising suggestively from behind his companion's considerable belly, and is rendered with an unsubtle bulge in his breeches. The man in blue has a similar bulge, while the presence of two companions further affirms his prowess.

So, what was going on in May 1793 to inspire this print? A rash of pregnancies? A boom in population? The title is a significant clue: it turns out that possibly none of the women in the image are actually pregnant; rather, they are wearing items known as belly pads which make them appear so.

While the print emphasizes this effect of wearing a belly pad, it not, apparently, the original intention. Instead, as Amelia Rauser has argued, wearing a belly pad was an attempt to create the kind of form familiar from Neoclassical statuary--an elegant, natural silhouette swelling gently under flowing robes cinched below the breasts (see Rauser's article for the many other prints and pieces of satirical writing on this trend). Even so, the effect was, as one observer put it, to make them "appear five or six months gone with child."

The central figures in white and pink and green are therefore examples of the way the fashion is meant to be worn (and also, perhaps, suggest what five to six months of pregnancy might look like in these styles). Indeed, the woman in white seems to be one of the originators of the trend, Lady Charlotte Campbell and her companion is probably her friend, the new Lady Abercorn. Notably, Campbell and Abercorn are also the only women (beside the little girl) unaccompanied by men, divorcing the shape of their bodies from the immediate context of a heterosexual relationship.

The problem, as Rauser puts it, is in moving from two-dimensional renderings (drawings, prints, plaques, frescos, engravings) and static three-dimensional representations (statuary) to the living, moving body. The print illustrates these difficulties by demonstrating how easily the elegance of Campbell and Abercorn gives way to excess.

While at first glance this may appear to be a fairly generic satire on a fashion trend amongst elites, many of the figures are actually identifiable. Additional meaning is brought to light by understanding how celebrity is operating in the image.

Starting on the left, the man in blue is George, Prince of Wales. On his left is his partner of many years, Maria Fitzherbert, whom he illegally married in 1785 (having not gained his father's permission as was required by the Royal Marriages Act of 1772). Marriages or partnerships that fell outside the law or involved partners of unequal social ranks were sometimes referred to as "left-handed" marriages, so her placement is not incidental. Fitzherbert was Catholic and twice-widowed when they married, and was often identified in satirical prints using a cross or crucifix as well as her well-known profile. Her condition as represented here raises questions, for there were constant rumors about her possible children by the Prince. Rather than a cut-and-dry case of a poorly managed accessory, her presence suggests one of the dangers of the trend: that it allows sexual guilt to hide in plain sight.

The woman on George's right is Frederica, the Duchess of York. Frederica's height was one of her more distinctive features, and is made much of in prints around the time of her marriage. A Prussian princess, Frederica married George's younger brother in 1791, but hopes that they would produce the needed heir to the British throne were waning. The couple would officially separate shortly after the print appeared, heightening the pressure on George to contract a legitimate, political marriage. Thus, her gesture to her belly probably indicates a desire for legitimate offspring rather than an existing pregnancy. The prince, meanwhile, divides his attention: his left hand is intertwined tightly with Fitzherbert's, yet he gazes upon the woman whose marriage and pregnancy he hopes would prevent his own. Frederica, in turn, looks at Mrs. Fitzherbert, imagining the condition in which she hopes to be.

There is another group of three in the background of the picture's right-hand side, and the women are identified as Mrs. Hobart, a society hostess known for her high-stakes gambling tables, and Lady Archer, another gambler (one of the "Faro Ladies") who also hosted illegal games. Their identities come from Hobart's size, often the subject of ridicule in such prints, and Archer's riding habit. Both women were older at the time of the print, and often objects of derision in satires; their inclusion in this print uses their pregnant forms (and Archer's aggression) as an indicator of the foolish excesses with which they were associated.

Finally, the couple in the foreground on the right are Lady Cecilia Johnston and (probably) George Hanger, whose cudgel was a familiar symbol from other prints. Hanger was a favorite of the Prince of Wales, and a well-known womanizer. Johnston one of the elderly aristocratic women whose outspoken ways were the topic of satire at the time. Why these two are paired together in unclear, but continue to emphasize how this fashionable trend of belly padding becomes ridiculous, creating pregnancy when there is none, concealing illegitimate pregnancy, disguising corpulence, and giving older women the illusion of a youth they are now beyond.

The complexities of wearing the pad well soon gave way to the more familiar empire-waist style that would dominate for the later 1790s and well beyond. By using shorter stays, eschewing restrictive foundational garments, and using fabrics that draped well, women took advantage of their own shapes to become these living statues, rather than relying on artificial manipulation.

So the cover image of my book is a bit of a red herring. But it reads as a bevy of pregnant women taking part in a public activity and therefore quickly makes one of the foundational points of the book: that pregnancy was a common sight, including among actresses in the eighteenth-century theatre. And it demonstrates that modern viewers can read the bodies of these women in the way the satirist intended without specialized knowledge. These historical bodies are legible to us with some of the same signals we use today: a rounded silhouette, a hand resting on or gesturing to a belly, changes in posture and gait. It thus speaks back to assumptions that audiences would be unable to recognize the pregnant bodies of performers beneath the layers of fabric they wore. Finally, by understanding the figures in the image, we come to understand that in real ways this image is a depiction of celebrity pregnancy in the eighteenth century. As identifiable public figures, the image evokes the same layered readings of body, identity, and immediate context that form the heart of my analysis of other women's lives.

We of course considered other cover options, but you might be surprised at how few pregnancy portraits exist for this particular time period in Britain, including exactly zero of actresses.* In addition to this image and another lampooning the same trend, I offered the publishers medical images showing the progression of pregnancy as an alternative; I think I even suggested we might photoshop a belly into a famous portrait of Sarah Siddons or Dorothy Jordan.

Ultimately, however, I could not be more delighted by this cover design--the cropping of the image capitalizes on the range of silhouettes the print offers, and uses the belly-parrot and the whip woman to draw potential readers in. The patterning on the title block evokes theatrical curtains, and the whole thing, from color scheme to font selections creates a pleasing "pick me up" feel. I cannot wait to share it with everyone in January!

--

*there's an amazing image of a retired Russian serf actress, Praskovia Kovalyova-Zhemchugova, during late pregnancy.

Comments